Sunday, August 8, 2010

Time to Move On

Thanks for reading,

Pat

Saturday, June 19, 2010

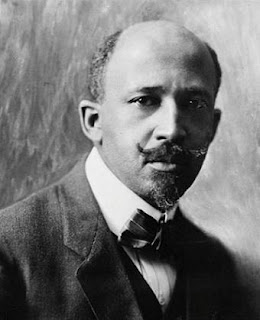

Du Bois' Lincoln

If your reading this blog post that means I passed comprehensive exams and I'm ABD--the proof of which is finally here:

Since I finished all of the writing required for the comprehensive exams, I didn't feel like jotting down much about Lincoln. Thus, the gap in the updating of the blog. Something that came up during the course of that week in trying to elaborate "my Lincoln", was W.E.B. Du Bois' Lincoln. In particular, there are two short pieces from the NAACP publication The Crisis which Du Bois wrote that I've been grappling with. Both of these articles were republished in Du Bois' Writings. Du Bois wrote "Abraham Lincoln" (May) and "Again, Lincoln" (September) for the magazine in 1922. That was a symbolic year to be writing about Lincoln as the Lincoln Memorial was dedicated in Washington, D.C. on May 30, 1922. That "temple" as we should remember was dedicated not to Lincoln as emancipator but as the savior of the Union. The seating arrangements at the dedication were segregated. By this time, Re-Union had come at the price of sacrificing integration. President Harding had already been chastised by Du Bois in The Crisis earlier in the year. Du Bois' words about Lincoln from May (published in July) no one writing about the 16th President should avoid considering:

"Abraham Lincoln was a Southern poor white, of illegitimate birth, poorly educated and unusually ugly, awkward, ill-dressed. He liked smutty stories and was a politician down to his toes. Aristocrats--Jeff Davis, Seward and their ilk--despised him, and indeed he had little outwardly that compelled respect. But in that curious human way he was big inside. He had reserves and depths and when habit and convention were torn away there was something left to Lincoln--nothing to most of his contemners. There was something left, so that at the crisis he was big enough to be inconsistent--cruel, merciful; peace-loving, a fighter; despising Negroes and letting them fight and vote; protecting slavery and freeing slaves. He was a man--a big, inconsistent, brave man"-p. 1196.

In September, Du Bois found himself confronted by responses to the above description of Lincoln. Du Bois found that people did not want to have a complex Lincoln. Nor did they tend to look at great historical personages with warts and all. "As a result of this, no sooner does a great man die than we begin to whitewash him. We seek to forget all that was small and mean and unpleasant and remember the fine and brave and good." What distinguished Lincoln as opposed to Washington for Du Bois was Lincoln's inconsistency and difficulties. As he put it, "The scars and foibles and contradictions of the Great do not diminish but enhance the worth and meaning of their upward struggle." pp. 1197, 1198. To his detractors, Du Bois asked if he had gotten the facts of what he said about Lincoln wrong. Well, he did.

Granted, Du Bois did not get everything wrong about Lincoln. The facts that were false still carry a symbolic meaning narrative. That is to say, despite Lincoln's shortcomings and inconsistencies, he was big enough to become Abraham Lincoln. However, just for the record, Seward didn't hate Lincoln and became one his closest advisors. Lincoln also was not of illegitimate birth. The Lincoln family was not as poor or Southern as it might come off from Du Bois' description either. There are things Du Bois' characterization left unsaid, but it can still serve as a starting point in trying to determine how Lincoln's inconsistency was both an aid and a hindrance, and, how it made him who he was.

Tuesday, May 11, 2010

Comprehensive Exams Are Approaching

In the meantime I do have some idea about the general areas the questions might come from, with my anticipations in brackets, to be thinking about: my Lincoln (i.e., why Lincoln and what do I want to say about him?), representations of Lincoln (what genres has Lincoln been depicted in and how has it been done?), the counterfactual Lincoln (what if he had lived?), Lincoln's use of religious symbolism (Lincoln was not a doctrinal religious person, why might he have used familiar symbols?), and Lincoln in African American memory (how has Lincoln been remembered by this community?).

I'm going to try to answer all of the questions in a manner which elaborates what I want to say about Lincoln (the more I figure this out now, the less I'll have to figure out later). I'm also hoping to come up with a title for this project during the course of the week. I'll be listening to music the entire time so perhaps something will stand out from a lyric or something I write. I haven't decided to make a playlist since I have enough music that tracks would still be playing a few months from now if I hit play and kept my computer from shutting down. Classical music won't help with the process of coming up with a title, but I'll likely listen to it anyway. I was listening to Sousa earlier and right now, this:

If my answers to the questions are any good, I'll post the main thrust of them after comps are over.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

The Progress Report

My dissertation proposal defense was held last Friday (April 16). The verdict of the committee (3 political scientists and 2 historians) was that I passed the defense and will move on to the comprehensive exams. Those exams will take place in May.

The comprehensive exam questions will help in deciding on the framework. Until then I'll be buried in source materials trying to preempt the exam questions (which I don't know yet). A brief description of how comprehensive exams work: Each of the committee members gives two questions, pick one; Write 25 pages per day per question; Two (2) days to edit said pages; Hope you made some sense during the week and have retained your sanity. Added degree of difficulty: I have to start teach my American Politics summer course the day after comps end.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Lincoln Looks West (Book Review)

Richard W. Etulain, ed., Lincoln Looks West: From the Mississippi to the Pacific (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2010).

With his contribution (a highly detailed and nearly 60 page biographical essay) Etulain does more than give the standard editor’s introduction to a volume where a little bit about the content of the chapters is relayed to the reader. He handles that perfunctory task in the very brief Preface. Etulain’s essay is masterfully done and is bound to help the reader see Lincoln as a “virtual founding father of western politics” (p. 33). Lincoln was able to dole out patronage positions in the 11 western territories, three of which (Arizona, Idaho and Montana) were organized during his presidency, and four States, including Nevada which came into the Union in 1864. Etulain charts a course of Lincoln’s manifold engagements with the American West from the 1840s to the assassination in 1865. Whatever one thinks about Lincoln and the West as seen through this nexus, it is easy to agree with Etulain that “among Lincoln’s many designations, he deserves to be known as a Man of the West” (p. 58).

Each of the essays in the book discusses significant aspects of Lincoln’s relationship with the West. Only two of the chapters are newly written work (Michael S. Green on Lincoln’s views on western issues in the 1850s and Paul M. Zall on Lincoln’s friend and “junkyard dog” in the Pacific Northwest, Dr. Anson G. Henry). All of the other chapters have been reprinted so on the whole, if one is up to date on the scholarship regarding Lincoln and the West from the last two decades (note: two of the essays are much older and date back to the 1940s), this volume will be a disappointment. For everyone else, this book will be thought provoking. The contributions themselves deal with Lincoln’s views on Mexican War, Lincoln’s dealings with western territorial appointments, Lincoln’s differences with Mormons on equality, and Lincoln and the Indians.

The weakest chapter of the group is that of Earl S. Pomeroy on Lincoln, Nevada and the 13th Amendment. The piece is five pages long and is nothing more than a corrective note. It tells us that, beyond a story told in print in 1898 by journalist Charles Anderson Dana, there is no reason to believe that Lincoln wanted to tie the admission of the State of Nevada to the passage of the 13th Amendment.

In stark contrast, David A. Nichols’ chapter on “Lincoln and the Indians” will likely startle general interest readers and deserves an overview here. Lincoln historians of course know all about Lincoln’s Indian policies—the fact that they are almost altogether mum on the policies, notwithstanding. Nichols’ piece is a summation of his underappreciated book from 1978, Lincoln and the Indians. Nichols details Lincoln’s unfamiliarity with the Indian System, his initial abandonment of the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) which led to Confederate intervention and a refugee situation in Kansas, and his management of the aftermath of the Dakota War of 1862 in Minnesota. Lincoln handled Indian affairs patronage positions as if they were any other political plums he had at his disposal to issue. Some of his Indian agents had never even met an Indian. In the Indian Territory, Lincoln did nothing to combat the rumor spread by the Confederates that the Federal Government would take the Indians’ slaves. The Cherokee Nation, for instance, split in two. Some Cherokees followed Stand Watie in joining the Confederacy and others led by John Ross supported the Union. Still, there were others who fled the Indian Territory altogether for Kansas. The other issue was the uprising by a branch of the Sioux who were cheated out of their annuities in Minnesota. Three hundred and three Sioux had been convicted of rape and murder in trials “averaging only ten to fifteen minutes per case” (p.216). The Minnesotans wanted to purge their State of all the Indians within their borders whether they had taken part in the violence or not. After trying to delegate the authority over the death sentences, Lincoln reviewed each of the cases personally. He ultimately reduced the number of executions to 38—which is still the largest mass execution by the government in United States history. Lincoln agreed to have Indians in Minnesota and Kansas removed to reservations. This policy resulted in the deaths of far more Indians than the 38 Sioux men who were executed at Mankato, Minnesota in 1862. Indian suffering and death were also implicit in Lincoln’s three major western policies: the transcontinental railroad, the Homestead Act and mineral development. All three plans for developing the West took place on lands where Indians lived and it was the policy of the government through the creation of reservations to get the Indians out of the way of “progress.” The same Lincoln who was engaging in total war in the South “was obsessed with a goal and would use violence to resolve problems when Indians, or anyone else, forcibly got in the way of his highest priorities” (p. 227).

Mark Neely’s essay gives us a Lincoln who was not precluded from a chance of reelection to the House of Representatives by opposing the Mexican War, but instead a Lincoln who was tired of the office. Neely tries to demonstrate Lincoln’s criticism of President Polk could not have hurt his career because his constituents never heard about it. This lack of recognition in turn frustrated Lincoln who was then ready to return to his law practice in Illinois.

Michael Green gives us a glimpse of how the West formed Lincoln politically as he tried to determine its future. Green focuses on the crucial decade of the 1850s where Lincoln would develop and refine the antislavery arguments he would use in the Cooper Union Address—the speech Harold Holzer said made Lincoln President.

Larry Schweikart’s chapter about Lincoln’s engagement with the Mormons is the least straightforward of the bunch as he is influenced by but not wholly in agreement with the West Coast Straussian Harry Jaffa. Like Jaffa, too much of what Schweikart writes is tangential to Lincoln. For example, he discusses the extent to which Lincoln was an Aristotelian—no major Aristotelian philosopher, let alone Aristotle himself, is mentioned in Lincoln’s Collected Works. By contrast, Euclid, the Greek thinker Lincoln was most familiar with, appears only six times. Schweikart’s emphasis is on the distance between and Lincoln’s views and that of the LDS Church on equality and slavery. Lincoln’s strategy was to cut off Mormon antipathy by leaving them (and Brigham Young in particular) alone. This move greatly improved relations between the Utah Territory and the Federal Government. Lincoln’s policy extended as far as not enforcing the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862 in Utah.

Lincoln Looks West is an important contribution to Lincoln scholarship and deserves a wide readership. The essays in it will aid even general readers in understanding how important the Trans-Mississippi West was to Lincoln and how he tried to shape the West during his presidency. Lincoln’s obvious connections to the West have been not been given enough attention over the years which necessitated the creation of this book. Lincoln Looks West does us a great service in moving us toward a more complete image of Lincoln.

Contributor List and Essay Titles

Richard W. Etulain “Abraham Lincoln and the Trans-Mississippi American West: An Introductory Overview”

Mark E. Neely, Jr. “Lincoln and the Mexican War: Argument by Analogy”

Michael S. Green “Lincoln, the West, and the Antislavery Politics of the 1850s”

Earl S. Pomeroy “Lincoln, the Thirteenth Amendment, and the Admission of Nevada”

Vincent G. Tegeder “Lincoln and the Territorial Patronage: The Ascendancy of the Radicals in the West”

Deren Earl Kellogg “Lincoln’s New Mexico Patronage: Saving the Far Southwest for the Union”

Robert W. Johannsen “The Tribe of Abraham: Lincoln and the Washington Territory”

Paul M. Zall “Dr. Anson G. Henry (1804-1865): Lincoln’s Junkyard Dog”

Larry Schweikart “The Mormon Connection: Lincoln, the Saints, and the Crisis of Equality”

David A. Nichols “Lincoln and the Indians”

Sunday, February 28, 2010

The Lincoln Assassination and Modern Comedy

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Lincoln, Davis and the Beginning of the War

The presidencies of both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis were enveloped by a war of unprecedented scale in American history. The war consumed the lives of both men as they worked long hours and poured over even minute details of the massive struggle. Lincoln and Davis were adversaries working at cross purposes. Lincoln aimed at keeping the country intact by suppressing a rebellion while Davis sought to establish independence for the Confederacy. Obviously, the nature of this relationship merits Davis a place in talking about the memory of Lincoln. However, without looking at a dual biography of Lincoln and Davis or a more specialized work on the Civil War, Davis is largely missing from the Lincoln narrative. He is confined to a few predictable reference points in Lincoln biographies. Each of these instances is telling in how they frame Lincoln and how little they tell us about Davis.

Lincoln’s farewell address in Springfield happened on February 11, 1861. Jefferson Davis would be inaugurated as President of the Confederate States of America seven days later. Lincoln would have to wait another two weeks for his own inauguration. Even if we are told that Davis was inaugurated while Lincoln was making his way East, Davis’ own farewell address to the Senate on January 21, 1861, is not often analyzed in Lincoln biographies. What does Davis speech contain?

Davis tells us in that speech that, as Mississippi has seceded he is (as a citizen of that State) “bound by her action” and must also depart. He notifies the packed house that Mississippians believed that they “are to be deprived in the Union of the rights which our fathers bequeathed to us.” About the seceding States, Davis says “we but tread in the path of our fathers when we proclaim our independence, and take the hazard.” Davis is not making a pretentious claim. His father and uncles fought against the British in the American Revolution. Davis’ older brothers were with Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans. Davis himself had escorted the captured leader Black Hawk to Missouri during the Black Hawk War and later became a war hero at Buena Vista during the Mexican War. As the Secretary of War in the Pierce administration, Davis tried to modernize the weaponry and professionalize the fighting force Lincoln would inherit a few years later. There is no reason to believe Davis was being less than earnest about his own feelings about exercising the rights he had fought and bled for. He does not say anything about seceding to save the institution of slavery though Mississippi certainly did in its “Declaration of Causes which Induce and Justify Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union.” The State Convention announced: “There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.” Davis did spell out this same sentiment in speaking of Lincoln and the Republicans on January 10 (the day after Mississippi seceded). “Your platform on which you elected your candidate, denies us equality. Your votes refuse to recognize our domestic institutions which pre-existed the formation of the Union—our property which was guarded by the Constitution.” In recalling these statements, more force is given to Lincoln’s words in Springfield: “I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington.”

By the time Lincoln addressed his well wishers in Illinois, seven states—all of them as convinced as Mississippi that Lincoln’s election meant slavery would be attacked—were already claiming to be out of the Union. Lincoln had to be exasperated at the incredulity of these states. He was anti-slavery to be sure, but was never an abolitionist. His nascent Republican Party was not an abolitionist organization. The party platform of 1860 reflected this fact. It only mentioned slavery in relation to the territories and the party’s interest in stopping slavery from spreading to the territories—certainly an anti-slavery position but not an abolitionist one. Lincoln had tried to reassure Southerners in his Cooper Union address in February of 1860 that while his party would continue to call slavery a wrong, Republicans were not in favor of rooting out the institution in the slave States. Lincoln did not blame Southerners for thinking that slavery was right and good, “but,” he said, “thinking it wrong, as we do, can we yield to them?” Lincoln then answered the interrogatory negatively. He was not about to yield now that seven State conventions decided to finally attempt the secession which Southerners had threatened to try for many years. As Lincoln saw it, he was the President of all the States which had cast their votes for President in 1860, even of six of the seceding States (South Carolina had no popular vote in 1860) which had refused to put his name on the ballot. While Lincoln won less than 40% of the popular vote, he had easily tallied more electoral votes than the other three candidates combined. Though he never used the phrase, Lincoln saw the Southern refusal to accept the results of the election as sour grapes (Davis in his First Inaugural noted that the States forming the Confederacy decided that the goals in the Preamble to the Constitution were not being met by as shown by their “peaceful appeal to the ballot-box”). Davis reached out to Lincoln in late February “animated by an earnest desire to unite and bind together our respective countries by friendly ties.” Lincoln would never acknowledge the existence of the Confederacy as a country, especially not in the various peace conference proposals during the war, and delivered an Inaugural Address which denounced secession but described the seven States in rebellion as “not enemies, but friends.”

Lincoln described secession as “the essence of anarchy” in his First Inaugural Address. Lincoln spoke not only of the Federal Union but of any government where a majority of its constituent society decides who will govern. In the case of the United States or in the case of the Confederacy which the Southerners sought to establish, when a minority refuses to participate in a political formation any longer because it dislikes the result of an election, the entity is destroyed if the majority which has fairly won the election lets the minority leave—such was Lincoln’s message and warning about the logic of secession. Lincoln toned down the originally drafted belligerent ending of his Inaugural: “shall it be peace or a sword?” while retaining the admonition that “You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.” The Confederate government ordered Beauregard to “reduce” Fort Sumter if it was not abandoned by Major Anderson. In the process of reducing it, the Confederacy fired the first shots, and in Lincoln’s retrospective words from the Second Inaugural Address, “the war came.” In remembering Lincoln and the start of the Civil War, we should not forget Davis. Even though Lincoln and Davis never met, they are inextricably bound together.